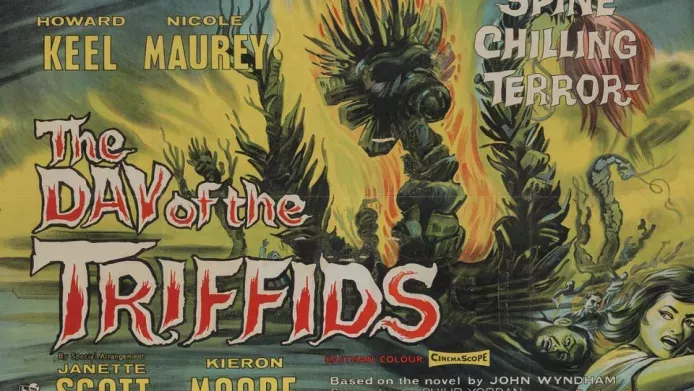

'All plants move, but they don't usually pull themselves out of the ground and chase you'

So begins the 1962 film adaptation of John Wyndham’s classic catastrophe novel, The Day of the Triffids, in which humanity is overwhelmed by an invasion of deadly whip-wielding weeds.

Triffids may not be real, but fears about invasive weeds most definitely are.

'Invasive alien species' are recognised under international law as one of the greatest threats to global biodiversity, human wellbeing and prosperity.

They are blamed for crowding out native species, degrading ecosystems and driving extinctions, with an enormous economic cost estimated at £1.7 billion per year in the UK alone [1].

While there is good evidence that invasive alien species can cause significant harm, it has also been argued that the risks have been overstated and reveal as much about our own prejudices and preferences as the species themselves.

Naming a plant a 'weed' is a complex issue, and there are benefits to many plants we traditionally consider to be weeds.

What is an invasive alien species?

Native species are those that arrived in an area without human intervention. Alien species are those introduced by people, intentionally or otherwise, at some point in the past. In the UK, we typically divide alien plants into two categories.

Archeophytes (ancient plants) were brought here before 1500 CE, often thousands of years ago, and include familiar weeds and wildflowers like poppies (Papaver rhoeas), cornflowers (Centaurea cyanus) and scentless mayweed (Tripleurospermum inodorum).

Neophytes (new plants) arrived more recently and include the butterfly bush (Buddleja) and Rhododendron.

Definitions of 'invasive' vary, but generally include plant species able to spread and cause damage to native habitats or natural processes on which people depend.

An infamous invasive species: Japanese knotweed

The best-known invasive alien plant species in the UK is undoubtedly Japanese knotweed (Reynoutria japonica), which has spread relentlessly since it was introduced as a garden plant in the 19th century.

Japanese knotweed has dense leaves that crowd out other plants, exceptionally strong stems, and creeping roots able to undermine foundations and walls, lift pavements and fracture drains. This damage is estimated to cost the British economy £166 million each year [1], with huge sums spent on control and eradication programmes that have, overall, failed to prevent the continued spread of the species throughout the UK.

Like any weed, Japanese knotweed has done well because we have provided the perfect conditions for it to thrive. Rough ground around our railways, roads, rivers, industrial sites and neglected parks mimic its native home in disturbed volcanic habitats in China and Japan, with plenty of opportunities for root fragments to break off and be spread by rivers or the illegal movement of infested soil.

Japanese knotweed is a classic example of a weed being 'a plant in the wrong place'.

Japanese knotweed is a classic example of a weed being 'a plant in the wrong place'. In its native Japanese volcanic habitat, knotweed is kept in check by repeated coverings of volcanic ash and landslides that limit the plants growth. It grows as part of an ecosystem of similarly vigorous plants and is surrounded by natural pests, both of which work to stop it from becoming the destructive weed it is here in the UK.

Not all alien plants are a problem

Aggressive species like Japanese knotweed make headlines, but not all alien plants become invasive. There are hundreds of introduced species in the UK that don’t cause significant problems. In fact, many archeophyte plants were once regarded as a major threat to agriculture, but modern farming practices mean many have become extremely rare and are subject to intensive conservation and restoration efforts.

The cornflower was one such weed, as observed by the poet John Clare in 1825, who described:

'...the blue corn bottles crowding their splendid colours in large sheets over the land and "troubling the cornfields" with destroying beauty.'

Cornflower populations have since declined drastically in the wild, leading the plant to be classified as ‘Endangered’ for a time.

While some neophytes like Japanese knotweed are undoubtedly problematic, less competitive species have arguably become positive additions to the UK flora.

For example, snowdrops (Galanthus) seem so at home in our hedgerows and woods that they are often assumed to be native and are one of our most loved and easily-recognised wildflowers.

Sycamore (Acer pseudoplatanus) is another neophyte often assumed to be a UK native and is valued for its ability to provide shelter in exposed coastal and hilltop areas. Sycamore trees are also controlled as a weed in some semi-natural woodlands.

So the extent to which alien plants are viewed as invasive is linked partly to their natural ability to spread, but also to where they occur and how useful or beautiful they are perceived to be.

Native plants can cause issues too

UK native plants are rarely described as invasive, but they too can spread to dominate and damage habitats.

For example, tor grass (Brachypodium pinnatum) has become a significant problem in chalk grassland, creating dense, spreading patches that are disliked by grazing animals and crowd out less competitive plants. Like Japanese knotweed, tor grass is taking advantage of its situation, where reduced grazing has provided an opportunity for the unrestricted growth.

There are other potentially problematic UK native species, including bracken (Pteridium aquilinum), which spreads rapidly in woods and moorland to crowd out surrounding vegetation, and birch trees (Betula), which can quickly colonise heathland.

Do we really need to treat native and alien plants differently?

It is a mistake to assume all alien plants are bad and all native plants are good in all situations, but there are good reasons for considering the two groups differently.

Alien species have left behind the competing plants, animals, parasites and pathogens that would naturally keep them in check, giving them a competitive advantage if the growing conditions are good compared with native and longstanding ancient plants that have grown up with our ecosystems.

The long-term consequences of new introductions are hard to predict and even harder to put right when things go wrong.

Many alien arrivals will have little impact, but our ecosystem is complex, where the long-term consequences of new introductions are hard to predict and even harder to put right when things go wrong.

It is therefore sensible to follow the precautionary approach that guides nature conservation in general. We should always minimise risks to the environment, even if we are not sure exactly how great these risks are.

This means never introducing plants to existing natural areas, particularly nature reserves or sites containing rare species and habitats, unless this is being done under expert ecological supervision.

We should think carefully about whether the plants in our gardens, parks and other green spaces are at risk of escape and make sure we manage and dispose of potentially invasive material responsibly.

Finally, if you can, find a space for UK native weeds and wildflowers in your life. They look beautiful, benefit wildlife and definitely won’t chase you down the street!